Overview

The shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) has the largest range of motion of any joint in the human body. This high degree of range of motion relies on a complicated anatomical system of muscle, bone, and soft tissue that provides stability while allowing a high degree of range of motion. The shoulder ball (humerus) and socket (glenoid) have little inherent stability; the humerus rests on the glenoid like a golf ball would on a tee. The lack of inherent stability results in a glenohumeral (shoulder) joint that is prone to instability and dislocation.

To add stability to this inherently unstable joint, the body relies on a fibrocartilage tissue that forms a ring around the glenoid called labrum. Labrum in turn is connected to capsule that links the socket loosely to the ball. Along with the muscles of the shoulder, this capsule/labrum complex affords stability to the glenohumeral joint. Injury to this capsule/labrum complex or congenital laxity of the shoulder causes a patient to have shoulder pain and instability (dislocation or subluxation). A shoulder instability event can be a true dislocation requiring sedation and a reduction of the shoulder in the emergency room. An instability event can also be a subluxation of the shoulder during which the shoulder slips in an out of socket without completely dislocating. Damage to the labrum and capsule is common occurrence as a result of an instability event; the damage causes the labrum to detach from the glenoid and predisposes the shoulder to further events of instability and dislocation. The most common direction of shoulder instability is anterior.

Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Dislocation

When the ball of the shoulder joint (humerus) comes out of the socket (glenoid), this is termed a shoulder dislocation; the golf ball has fallen off the tee. Instability or dislocation of the shoulder can occur as a result of trauma or as a result of congenital laxity of the shoulder joint. A shoulder dislocation or subluxation that occurs without trauma is usually the result of multidirectional instability, discussed in a later section.

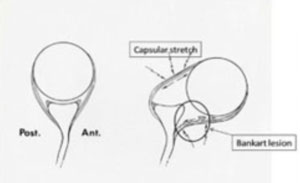

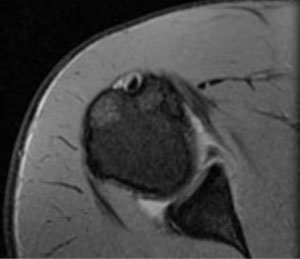

A shoulder that is acutely dislocated is usually reduced by a team physician, athletic trainer, or emergency room physician. A sling is then placed. The first line of treatment after a shoulder dislocation caused by trauma is a period of immobilization in a sling (1-4 weeks) followed by a rehabilitation program to regain motion and strengthen the shoulder muscles that provide stability to the shoulder. An MRI is usually performed to document the damage to the shoulder after a dislocation. After the shoulder has regained motion and strength, it is usually safe to return back to normal activity, including sports. If the shoulder remains painful or unstable despite adequate rehabilitation, surgery is often required to restore stability and decrease pain. The most common reason for a shoulder to remain unstable after a shoulder dislocation is a specific type of labral tear called a Bankart lesion. This lesion describes a labral tear that occurs from approximately the 3 o’clock position to the 6 o’clock position on the glenoid. This tear essentially ‘opens the door’ for more episodes of instability. These episodes of instability cause pain, apprehension, and dislocation. Figure 1 is an artist’s rendition of a normal shoulder joint as well as the trauma caused by shoulder instability depicted on MRI.

Figure 1. 1A: The ball (humerus) normally rests within the socket (glenoid) like a golf ball on a tee. When a dislocation or subluxation occurs, the glenoid labrum is torn from the bone and the capsule is stretched. These injuries can cause recurrent instability of the shoulder. 1B: MRI of the shoulder in a first time dislocator depicting a torn anterior labrum (acute bankart tear).

Figure 1A

Figure 1B

Workup Prior To Shoulder Instability Surgery

During a visit with Dr. Gamradt to evaluate for shoulder instability and/or labral tearing, one of the most important features of the workup is the History. A detailed injury history will be sought including how the shoulder was injured, the position it was in when it was injured, and whether sedation in the emergency room was required to stabilize (reduce) the shoulder. The patient will be evaluated as to how many times total and how frequent the instability events occur. Sports participation and previous treatments are also documented. After the history is taken a detailed physical exam is performed that helps determine the patient’s range of motion, strength, shoulder stability, and positions of apprehension. X-rays are important in ruling out fractures and cumulative damage to the shoulder from repetitive instability. An MRI will be performed usually with an injection of contrast in the shoulder joint to improve detail of the labral tearing present inside the shoulder. In cases of severe dislocation or repetitive dislocation, a CT scan may be ordered to determine if there has been damage to the bone on the ball or socket of the shoulder that precludes an arthroscopic operation to stabilize the shoulder.

Indications for Surgery in Anterior Shoulder Instability

Surgery is recommended in a shoulder that has persistent instability and pain despite an adequate period of rest, rehabilitation, and attempted return to full activity. Rarely, surgery may be recommended after a first-time dislocation in certain high-risk individuals (military, contact athletes, severe labral tearing on MRI scan). It is more common for a surgeon to recommend rehabilitation in most cases. The risk of recurrent instability in young patients (teens/twenties) after a 1st time dislocation is greater than 50%. If a second or third dislocation occurs, it is advisable to have shoulder stabilization surgery to minimize the risk of further damage to the shoulder labrum and bone. In cases of labral tearing without frank dislocation, the exact indications for surgery are less clear. Simply put, if the shoulder has failed 3-6 months of nonoperative treatment and remains painful and unstable with activity, surgery is probably warranted.

Arthroscopic Shoulder Stabilization Surgery

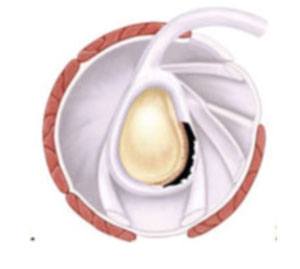

When the patient and physician have agreed that shoulder stabilization surgery is needed and warranted, the surgery is usually performed arthroscopically in the outpatient setting. An interscalene block (regional anesthesia) with or without general anesthesia is performed. Surgery is performed utilizing 3-4 small incisions with the help of the arthroscope. During the surgery, the labrum is visualized and freed from scar so that it can be mobilized into its normal anatomic position. Bioabsorbable suture anchors are then inserted into the glenoid bone; these anchors each have a suture that is used to reattach the labrum back to the bone. Three to four anchors are usually required to reattach labrum to bone in the setting of recurrent anterior dislocation. A sling and cold therapy device are placed in the operating room to use postoperatively. The following figures depict a typical arthroscopic anterior stabilization and labral repair.

Figure 2

Figure 3

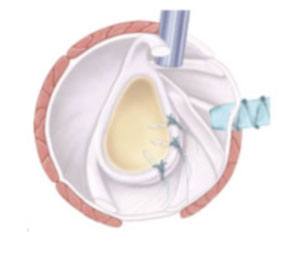

Figure 2. Bankart lesion with detachment of the glenoid labrum from 3-6 o’clock.

Figure 3. Artists rendition of a suture anchor repair of the labrum.

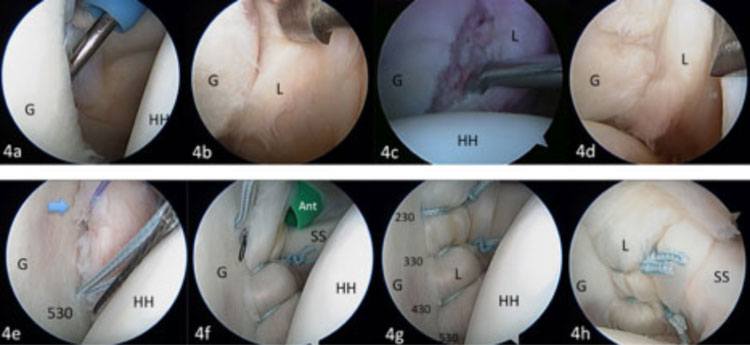

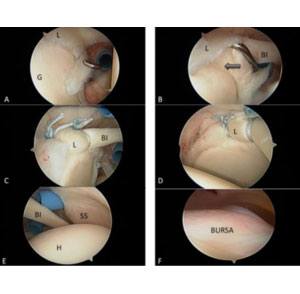

Figure 4. depicts arthroscopic pictures of a typical arthroscopic instability operation with labral repair.

Figure 4

Rehabilitation after Stabilization Surgery

Rehabilitation proceeds in a predictable stepwise fashion. Immobilization in the sling is usually required for 4-6 weeks. During the period of sling usage, gentle protected range of motion is initiated. From weeks 6-12 postoperatively, motion of the shoulder is restored to normal. Strength is regained between weeks 12-20 postoperatively and return to sports is usually 5-6 months after surgery.

Labrum Tear without Dislocation

(Posterior and Superior Labrum Tear)

Posterior and superior labral tears can cause a significant amount of dysfunction, pain, and limitation of activities, but they rarely cause dislocation. These are discussed together in the following section.

Posterior Shoulder Instability and Labrum Tears

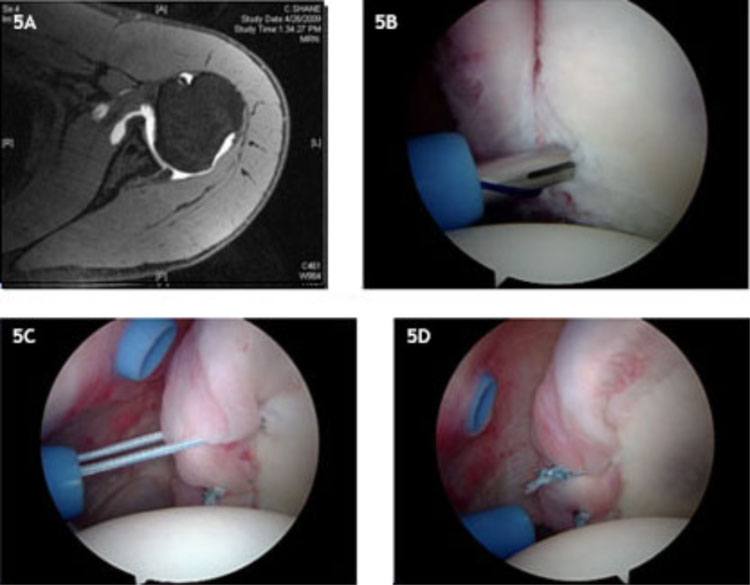

Injury to the posterior aspect of the labrum is less common than anterior tears. These posterior labral tears are common in athletics particularly in football linemen and other sports that subject the shoulder to a repetitive posterior force. These athletes commonly complain of a pain and subluxation alone rather than true dislocations. True posterior shoulder dislocations are rare and are caused by seizures, electric shock, and high energy trauma. Figure 5 shows a posterior labral tear on MRI and subsequent arthroscopic repair.

Figure 5

Superior Labral Tears

A superior labral tear or SLAP lesion, as it is commonly called, is common in overhead athletes as a cumulative result of years of wear and tear from sport. In addition, these tears can be caused by varying degrees of shoulder trauma including hyperextension, longitudinal traction, and falls directly on the shoulder. These tears do not commonly result in instability. Instead, the patient with a SLAP tear will commonly complain of pain with overhead activity, throwing, weightlifting, or any increase in vigorous shoulder activity. Figure 6 shows a superior labral tear on MRI in a throwing athlete and Figure 7 shows subsequent arthroscopic repair.

Figure 6

Figure 7

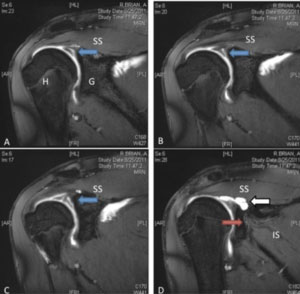

Arthroscopic Labral Repair (Superior or Posterior)

If the shoulder remains painful and limits activity despite an adequate course of rehabilitation and rest, arthroscopic surgery can be very successful in eliminating pain and improving function. Surgery to repair a torn superior labrum (SLAP tear) or a posterior labral tear is also performed arthroscopically using suture anchors. Similarly, the labrum is repaired back into its anatomic position on the glenoid using suture anchors. Immobilization in the sling is usually required for 4-6 weeks. During the period of sling usage, gentle protected range of motion is initiated. From weeks 6-12 postoperatively, motion of the shoulder is restored to normal. Strength is regained between weeks 12-20 postoperatively and return to sports is usually 5-6 months after surgery. Figures 6 and 7 depict typical arthroscopic surgery for these cases.

Multidirectional Instability

Certain individuals have a predisposition toward shoulder instability due to congenital ligamentous laxity. In these individuals, the shoulder instability events occur in the absence of trauma or seemingly mild injuries. An MRI scan in these individuals will often reveal little or no damage, only increased capsular volume and redundancy. In these individuals physical therapy is often very successful in restoring relative stability to the shoulder and surgery is only recommended for those patients failing to respond to 6 months or more of rehabilitation.

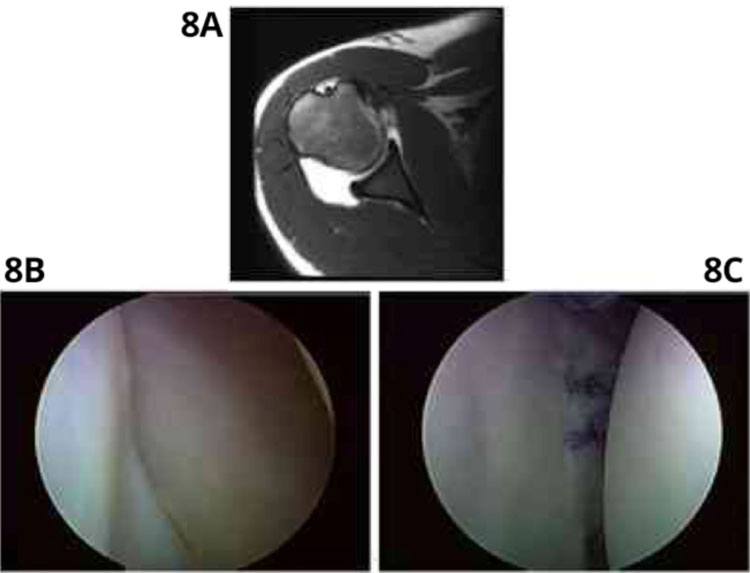

Surgery for multidirectional instability of the shoulder is performed arthroscopically as well. Surgery focuses on decreasing the redundancy of the capsular tissue in those patients with multidirectional instability. This is accomplished by capsular plication with or without suture anchors. Rehabilitation is similar to standard instability surgery. Figure 5 shows an arthroscopic placation of a shoulder with multidirectional instability without suture anchors.

Figure 8A: Typical MRI appearance of multidirectional instability; minimal labral damage but increased capsular volume. 8B: Arthroscopic appearance of a ‘drive-through sign’. The shoulder has increased capsular volume and attenuated labrum which is not torn. 8C: After arthroscopic capsular placation through the intact labrum with suture anchors, the capsular redundancy has been eliminated.

Figure 5

Rehab After Shoulder Stabilization / Labral Repair

A sling is placed in the operating room that must be used full time for 4-6 weeks depending on the severity of the injury and the quality of the repair. During this period of sling immobilization, gentle range of motion exercises are performed within a protected range. After discontinuation of the sling, range of motion restrictions are lifted and the patient works with the physical therapist to restore full range of motion. Strengthening exercises are begun after 3 months. Unrestricted return to sports usually requires 5-6 months.

Surgery for Failed Shoulder Stabilization or Severe Instability with Bone Loss: Latarjet Coracoid Transfer

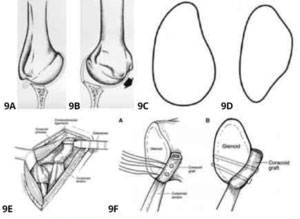

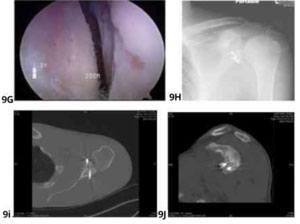

Occasionally, a patient will present with a failure of multiple attempts at surgical stabilization or a history of countless shoulder dislocations. In these patients, bone loss in the ball and socket joint often precludes a standard arthroscopic repair. In this setting, x-rays, MRI, and a CT scan are performed to determine the severity of bone loss and the quality of the soft tissue. If the bone loss on the glenoid side is too severe for arthroscopic stabilization to be effective, a Latarjet coracoid process transfer is usually indicated. In this open operation, a bone graft is harvested from elsewhere in the shoulder to restore the congruency of the shoulder joint and gain stability. Rehabilitation is similar to an arthroscopic stabilization although it proceeds at a slower place and may not result in restoration of full range of motion. Figure 9 depicts an artist’s rendering of the problem associated with multiple dislocations causing glenoid bone loss. Bone loss on the glenoid side is often treated with a Latarjet coracoid transfer.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 9A. Bone loss on the glenoid side of the ball and socket joint destabilizes the shoulder joint and causes recurrent subluxation and dislocation (9B). 9C: The normal glenoid has a pear shape and is wider inferiorly than it is superiorly. 9D: The glenoid takes on an inverted pear shape with increased bone loss and is wider superiorly than it is inferiorly. The resultant bone loss is not reconstructable with a standard arthroscopic approach. 9E: In a Latarjet coracoids transfer, the coracoid process is used as a bone graft to restore the normal shape of the glenoid and stability to the shoulder. 9F: The bone graft is secured with 2 screws on the anterior rim of the glenoid. 9G: Arthroscopic picture depicting antero-inferior glenoid bone loss with engaging Hill-Sachs deformity of the humerus and absent labrum. 9H: X-ray after Latarjet coracoids transfer. 9I and 9J: CT scan after Latarjet